| RECENT POSTS DATE 12/11/2025 DATE 12/8/2025 DATE 12/3/2025 DATE 11/30/2025 DATE 11/27/2025 DATE 11/24/2025 DATE 11/22/2025 DATE 11/20/2025 DATE 11/18/2025 DATE 11/17/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/15/2025 DATE 11/14/2025

| | | THOMAS EVANS | DATE 9/29/2011David Robbins--artist, comedian, writer--defines Concrete Comedy as "a comedy of doing rather than saying." On the occasion of his booksigning at the New York Artist's Book Fair (at MoMA P.S.1, Sunday 1 pm), Robbins talks to Artbook about his fantastic new book, Concrete Comedy: An Alternative History of Twentieth-Century Comedy.

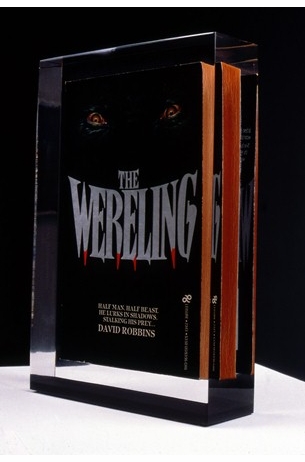

ARTBOOK: Concrete Comedy is the culmination of a line of inquiry and research that dates back some way in your career; its thesis also highlights your own conflicts with the shortcomings and blind spots of art culture. The book itself is certainly the best possible exponent of its argument, so I won't ask you to paraphrase it too much, but could you tell us about the earliest inklings of your conception of it, whether in your own work or that of others, or both?DR: It began as part of an effort to create a context for my own pictures and objects. I’m not an academic. The book grew from the character of my own art which, from the start, 1984, ’85 in New York, had somehow a psychology and intent different than the work of my peers. Many artists, when they're starting out, will try to fit themselves to the established template of How To Be An Artist, but for some it doesn't take--the template isn't usable. I hadn't gone to art school but through a chain of events I started exhibiting pictures and objects, and right from the start these had a more theatrical character than does standard visual art. Instead of being concerned with matters of representation, context, meaning, etc, I was doing an existentialist comedy act via objects. A comedic sensibility is a tricky thing to negotiate in the art world, which prefers weightier social, phenomenological, or philosophical subject matter--“importance.” Comedy is more narrowly intentional, it’s less absolutely open to interpretation than is art, it can’t be read in as many ways, so it’s perceived as lesser. It’s tolerated rather than celebrated. But I wasn’t concerned about that: my stuff was addressing as much a literary or theatrical mind as a visual art mind. I wasn’t working on art problems, I was working on comedy problems. I was trying to dig out from under a specific cultural inheritance--the cold ironic American media voice, which had become the dominant tone, had been for then going on twenty years, and had definitely outlasted its usefulness. I was volunteering to process cultural toxins that manifested in the prevailing comedic tone--David Letterman’s, people like that. Making fun of everything isn’t the way I want to spend my life. I’d rather use comedy to build something. The problem I was tackling was a problem of authorial voice, which is customarily something associated with writers rather than visual artists, but I was as much influenced by my contacts with humorists at The New Yorker--my mentor George Trow, Veronica Geng, Ian Frazier--as by my visual art heroes. A few hip commercial galleries showed and sold my stuff but, increasingly, I considered that through objects I was stretching the idea of comedy and contributing to the history of comedy rather than art. To characterize what I was doing as “comedy taken material form” rather than “funny art” seemed not only more radical but more accurate.Now, needless to say, exhibiting work which had this mindset and these aspirations carried a complicating effect, since the whole point of the art context is to set apart a place to show and consider art. That's the modernist line, anyway, and an entire industry of commerce, valuation, and interpretation has been built around it. It’s part of our cultural inheritance. But all the vested interests in the world can’t prevent the evolution or mutation of a read on a context. It ought to be possible--it is possible--to turn the modernist argument that “this is art because I the artist say it is” inside out: “this is not art because I the author say it isn’t. It’s something else.” In 1988, after Christian Nagel, then my German gallerist, introduced me to the work of early twentieth-century German comedian Karl Valentin, the game acquired still another level of complexity. As a comedian who made objects Valentin had approached the matter from the other side. Objects made with comic intent by a comedian--are these “art” or something else? What is a “comic object” anyway, and how is it similar to/different than an art object? From discovering Valentin I realized that my sensibility was part of a tradition, but one which hadn't been identified or structured. That inspired me to research the history of what I termed “concrete” comedy--the comedy of doing rather than saying--gradually identifying many examples of it, in all fields of communication, not restricted to either context, art’s or comedy’s. No history of this sensibility yet existed--if it had, I wouldn't have had to undertake putting it together. Ten years of research and writing resulted in an alternative history of twentieth-century comedy, the mere existence of which raises another batch of questions about how we identify and define comedy! By design the book destabilizes the assumptions and certitudes of more than one discipline.ARTBOOK: Can you identify some of these early objects you considered comic objects?I’ll give you three. First, a comic object: The Wereling--a book by a horror author also named David Robbins, encased in a solid block of lucite. Who is the author of this work, and what exactly is being authored? The Wereling is the perfect title for such a slippery, ambidextrous work.

The Wereling, 1985.

Second: a photograph taken in Times Square with a cut-out of then President Ronald Reagan.

Getting My Picture Taken With Ronald Reagan In Times Square, 1986.

Third example is not an object or image but an action: going fishing by myself on Loch Ness. You only know about it as a story I tell since I destroyed the film that I made of my adventure, so you have to decide to believe the story’s veracity, just as we all have to decide whether or not to believe that Nessie exists. None of these three efforts were physically very substantial or object-intensive. They were more like indicators of a cultural location, marked by a comic attitude.ARTBOOK: The objects of Concrete Comedy are partly distinguished from art objects as aids (“props”) to performance (“theater”), but that isn't a defining characteristic of them, is it?DR: The objects I was offering had art’s iconic language down, and were informed by conceptual art, but they didn’t engage the concerns of visual art or art history. The sense of theater preceded and overrode aesthetic concerns, in other words. This wasn’t something I’d thought out, it’s just instinctive and natural--strong evidence that some sort of cultural mutation or evolution is speaking through my actions. I’m trusting that. From the start I’m treating the art context as a stage on which to present a comedy act whose form is tailored to the grammar of that context--things that hang on the wall or sit on the floor. What I was interested to construct had nothing to do with the concerns of art, really, but I continued to present it within the art context because that’s the site where we engage and consider the real--where we try to get to the bottom of the Actual by focusing on material culture, hanging things on the wall or setting them on the floor--so by its nature that context was capable of supporting non-fiction comedy. I surmised that non-fiction comedy offered the best means of processing the cold ironic American media voice toward another, more constructive tone, because non-fiction comedy circumvented all the “let’s pretend” media--television, film--from which the cold ironic American media voice had issued and which also gave it continual reinforcement. The art context was the perfect place to transpose comedy into a different key and open something else up, which explains why I stuck with it despite the slights delivered by those such as the museum curator who, after looking through slides of my work some years ago, asked me, “Do you consider this a career?”

ARTBOOK: You identify two traditions within concrete comedy that both begin around 1915 with the activities of Karl Valentin (specifically his theater of comic objects called the Panoptikum) and Marcel Duchamp. With Valentin, a theater is invented from scratch—the Panoptikum was a delineated area containing comic objects, which Valentin further defined as a delineated area by giving guided tours of it--and with Duchamp the theater already exists but is designated as a theater: in his case, the theater of the context of art, the very existence of which he highlighted with the readymade. Why do you think these brilliant reconceptions of objects came along when they did?DR: We can’t know for certain. But the fact that we’re talking about an enormous imaginative leap in our relation to material culture is a clue, and if we trace that back it leads us, I believe, to the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution forced an enormous wedge of abstraction between ourselves and the made thing. Things that had always been made by hand now were manufactured by some machine somewhere. This development was a trauma for the generation that experienced it--jobs disappear, livelihoods disappear, old ways gone, what do we do now?--much as many people today are economically traumatized by the effects of the digital revolution. My thought is that there is the traumatized generation, mid-1800s, and then their children are required to deal with traumatized parents and also to begin re-building--no room for humor in the children’s situation either, right? But the next generation, in effect the grandchildren of the generation traumatized by the Industrial Revolution, early 1900s, for them the abstraction introduced by the Industrial Revolution is now a given, it’s a done deal. This is the generation that includes Valentin and Duchamp. On reaching maturity these two geniuses take the abstraction, the detachment, the distance from object-production and they start to toy with it. They see that very human things--including comedies--might be built using the abstractions that had been imposed on human identity by the machine.

ARTBOOK: After Valentin and Duchamp you recruit a massive array of practitioners of concrete comedy from across the past century. Readers approaching concrete comedy for the first time may be able to guess in advance a few of those included, such as Fischli & Weiss, Ernie Kovacs, Jacques Tati, Jeffrey Vallance, Ed Ruscha, Georg Herold and Maurizio Cattelan. But lest we mistake concrete comedy for purely object comedy, you also apply the term to any activity that renders an ostensibly real-life situation comically ‘concrete’ by altering its terms of belief. One example is your former employer George Plimpton’s occasional infiltration of professional sports teams as a complete amateur--quarterbacking for the Detroit Lions, pitching for the New York Yankees, even heavyweight boxing. He joined these teams not to win, but to encounter athletes he admired and also in the spirit of slapstick. Before we talk about this expansion of concrete comedy into objectless performance, do you have any stories about working for Plimpton? Did you ever assist him in these antics (which would seem like a dream job)?

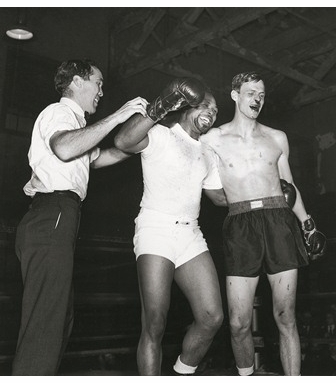

DR: Alas, George was fairly post-antic by the time I worked for him in the early 1980s, although his high spirits, energy, and merriness were certainly intact. My duties there were administrative--booking his schedule, running the office. Of course he was a very social and celebrated creature, with a wide circle of friends in many areas of life, so I enjoyed frissons of contact with various legendary figures whose names I needn’t include here. The only truly exciting assignment I carried out for George was quite somber and down to earth: traveling to two little Kansas towns, Holcomb and Garden City, to interview all the surviving In Cold Blood principles for his oral biography of Truman Capote. An unforgettable experience, as you might imagine. Warm and unexpectedly sophisticated people, out that way, incidentally. Terrific social skills, developed, I like to imagine, because in the old days the stranger brought news of the wider world, and the people with the better social skills could draw the stranger to their house, and get the news.Working for George, it was only natural to give thought to George’s work, specifically his adventures as a “professional amateur.” No doubt my exposure to him influenced how I’d later broaden my formulation of concrete comedy to include comic minds from well outside either the official art world or the official comedy world. George was a unique figure with a highly individualized and innovative take on comic performance, who identified a string of existing theaters--the National Football League, the New York Philharmonic, and so on--and joined each in turn, not as a destructive prankster but in order to write books about the experience. Because he was a writer, George has never been included in the canon of performance artists, but some of his activities certainly overlap, pre-date, or outdo theirs. Ultimately he’s idiosyncratic and wholly self-invented, an original. My book places him in the Duchampian wing of concrete comedy, where theaters are designated. In contrast to the Valentinian wing, where the theater-context is invented from scratch.

A bloodied George Plimpton still cheerful after a bout with boxing champ Archie Moore, 1959.

ARTBOOK: Could you explain how these interventions in pre-existing “theaters” relates to concrete comedy as we’ve discussed it so far (which is mostly as a kind of object comedy)? You also mention Andy Kaufman and the (contemporary) Improv Everywhere collective in this context…DR: Concrete comedy is broadly defined as comedy that’s enacted in real space and real time, for its own sake, in contrast to the illusionistic comedies of make-believe which are scripted for TV or film productions. Stand-up comedy too is illusionistic, by the way: via language, the comedian relates stories or observations which index off-stage situations or experiences that the audience mentally pictures. Almost all mainstream comedy is illusionistic, then, whereas concrete comedy is non-illusionistic. It’s just as real as you are, occupying the same space and time that you’re in.Concrete comedy is the comedy of doing rather than saying. A comedy of doing can take an infinite variety of forms. Concrete comedy can include the creation of a comic object à la Valentin, certainly, but it can also include behaviors--comic actions or gestures--that are carried out in the real space/real time setting of some public theater: the street, a football stadium, a department store, a wrestling ring, and so on. And where one comedy of doing might be a unique, singular event, such as Improv Everywhere’s meticulously planned invasion of Forever 21 department store windows fronting Union Square for a guerilla dance routine, another comedy might be gradually constructed in some public arena over time, such as Kaufman’s elaborate, multi-layered Memphis wrestling saga, which comedy took place over many months and manipulated not only the theater of the pro wrestling circuit but the television and press coverage that attaches to it. You see how far a definition of “public theater” can be stretched! Public theater isn’t limited to a single site but can encompass an entire context. The 1980s rock band The Replacements, for instance, constructed a collective comic persona via all the media apparatus of the rock music business--stage performances, recordings, press photos, music videos.... All the examples I’ve mentioned may use different materials to attain their ends but all are equally “lived for real” comedies, and in that way just as concretist as a comic object.

Improv Everywhere's Look Up More performed in the windows of Forever 21 on Union Square, 2005.

ARTBOOK: Inventing a subject and then writing its history seems a very fun thing to do, but it must also have been grueling to organize into a coherent account.DR: Figuring out how to do it was a big part of why the book took ten years to write. Concrete Comedy isn’t a work of scholarship, really. It’s not “building on the literature” because there is no literature to speak of! It’s made from scratch, with only the dialogue between my sensibility and a reasoning process to go on. What and who to include, and why? Is there a sense of theater in this gesture or object, and a certain courageousness in having made it, or is “a funny picture” the beginning and end of the thing? And what process has been engaged to produce it? Is it something made in a studio or is it out in the world, engaging the processes of the wider world and thus the theaters that attach to these processes? Is the person under consideration a concrete comedian, which interests me a lot, or “an artist who uses humor in his work,” which doesn’t excite me as much? I’m writing a history of comedy, remember, not of art. These are the sorts of questions I had to sort through, then apply. A ton of hairsplitting went on, as you can imagine.

Jeffrey Vallance with the King of Tonga, to whom Vallance has gifted a pair of swim fins, 1985.

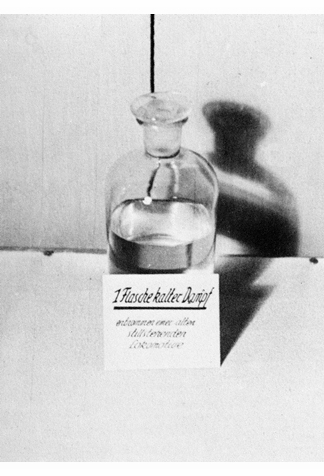

I also had to keep in play the distinction between “funny” and “comedy.” A comedy treats the world at a certain angle, and that treatment amuses and liberates us, but it isn’t necessarily funny in the way that something is that aims really to be funny. A “comedy” can be a very serious thing. Getting across a comedy can be a much more deliberative and constructed act than is something that’s quite evidently or directly funny. Identifying a comedy is far trickier and more challenging work than identifying funny.ARTBOOK: Earlier you described your work as “an existentialist comedy act via objects,” which conjures Pataphysics. Do you see sympathies between Pataphysics’ lovingly satirical treatment of the laws of the material world and concrete comedy?DR: When I was researching the book I looked into Pataphysics--“the science of imaginary solutions” as Alfred Jarry characterized it. But it didn’t stick. My take on Pataphysics is the same as my take on the Absurd, which is that the goal--the effect or sensation sought--is determined before the comedy and the comedy is then tailored to that goal. That’s putting the punchline before the joke, in a way, and that doesn’t interest me at all. Concrete comedy, by way of contrast, accepts and celebrates a wide range of goals and effects. Concrete comedy is a method of communicating comedic positions via real things and actions, and it accepts the imprint of as many personalities as there are practitioners. It’s not a philosophy. Philosophies of comedy are too “of their time.” They become corny in no time!ARTBOOK: You oppose concrete comedy to comedy that’s illusionistic, mentioning language as one means by which the humor is dispatched away from “here” and towards an “elsewhere.” Of course, many of the comic objects you cite are dependent on language for their comedy (Duchamp’s “Paris Air” and Valentin’s Panoptikum objects wouldn’t amuse us without their titles), and to what degree that language takes us “elsewhere” seems to be exactly a matter of degrees. In other words, one aspect of concrete comedy might be a comedy not of saying but certainly of naming. DR: Language isn’t at all necessary to a work of concrete comedy, but it can be useful--to indicate a comic attitude, to indicate intent, and to help focus our perception. My favorite example--because the elements comprising it are so stark and simple--is Valentin’s “Cold Steam of an Express Train Locomotive,” which is really nothing more than a plain glass flask half-filled with water. “Cold Steam” functions in what I like to call a proplike way. It’s not a true prop, because a prop merely supports a narrative that’s already underway, whereas with “Cold Steam...” there is no narrative--no theater--apart from that which the object itself supplies. Therefore it’s not a prop but instead proplike--a much more complex imaginative location. It’s an innovation with a ton of abstraction in it...--one of those imaginative leaps that helps define the modern, comparable in impact to Chanel’s little black dress or the way in which Elvis Presley’s singing style abstracted several musical traditions at once.

In the final analysis comedy is nothing more than an attitude toward the real. That’s all it is. An object like “Cold Steam” gives you the real, in the form of glass flask half-filled with water, and it also supplies the attitude, in the form of a little sign placed before the flask. The little sign gives the title, which indicates Valentin’s intentions--the theatricalization he has in mind. This is a very simple example, of course, yet as simple as it is, it’s still quite slippery, because it opens onto the semiotic realm of how words, images, and things perform. Lots of possible combinations in that...multiplied by the fact that there are as many different kinds of comic attitude as there are comic personalities.ARTBOOK: Can you say a little more about the term “proplike”? Isn’t a narrative for an object already underway once a context is declared for it—whether by a sign (such as Valentin’s little sign for “Cold Steam”) or by the theater beyond it (such as his Panoptikum)?DR: The proplike object functions as a sign of comedy, as something introduced at a comic angle into the theater of the world, as opposed to a prop, which supports a make-believe scenario. A place such as the Panoptikum is a space set apart to present a collage of proplike signs for comedy. It may be comic theater, okay, but it’s concretist comic theater. A comic theater founded on material culture was a huge advance. What is the narrative of the Panoptikum? There is none. Instead, it’s a sign pointing to the advance of the human imagination with regard to material culture. The real flows through a place like Valentin’s Panoptikum in a way that it doesn’t flow through a make-believe scenario. Valentin removed the stopper from the bottle, allowing the comic theater to begin to expand to the contours of reality.The Panoptikum is the earliest example of a theater of material culture. Concrete comedians subsequently learned to insert their theaters of material culture directly into the processes and systems of the wider world, uncontained by any proscenium arch--or if you prefer, absorbing the proscenium arch of context into the comic theater. In concrete comedy the comedy is as real as whatever’s being indexed. Enormous difference from mainstream comedy.ARTBOOK: One of the great pleasures of Concrete Comedy is its continual, fluid maneuvering from objects and persons designated “comedy” to objects and persons designated “art,” which really does allow the reader to briefly hang up both umbrellas--a very liberating sensation indeed. You said at the outset that the book began “as an effort to create a context” for a certain phase of your work; you’ve developed a broader context with the title and topic of your online book, High Entertainment. This is more than just a floating moniker, since you argue in the book that the digital revolution has already created such a thing as “High Entertainment.”DR: Ideas such as High Entertainment or Concrete Comedy are like culture apps. They’re oxygenating ideas, good for the cultural ecosystem.For readers who may be unfamiliar with the book, what I mean by High Entertainment is simply stated: Take the best aspects of the art and entertainment contexts--namely, art’s experimentalism and entertainment’s accessibility--and apply them toward a new synthesis. This isn’t pie-in-the-sky theory, it’s already happening. The digital revolution allows independent imaginations to experiment with mass media formats and distribute the results inexpensively. High Entertainment is a mutation--a type of creativity that doesn’t rely on either the production system of the entertainment context or the evaluative system of the art context. It’s an evolutionary step, already underway. We need to make the most of the opportunity it affords.Concrete Comedy similarly represents an evolution of our thinking about context. I’d contend that the very idea of pursuing a line of comedy within the art context, such as some of us have done, ought to be regarded as evidence of an emergent consciousness that perceives the art context not as the terminus point or limit of expression--the traditional view of it--but rather as but one production context available to an independent imagination at work within the larger cultural field. This mutation of perception was already present in my earliest exhibitions of comic objects in the mid-‘80s, when I instinctively positioned myself comedically rather than, in the art context sense, artistically. I didn’t know what I was doing, I was just doing it because it felt authentic. The Concrete Comedy book advances that instinct considerably, due not only to its subject matter of an invented alternative history of comedy but because as a book it enters the cultural stream in a way that art objects don’t. The author of these two kinds of communications occupies more of a cultural than an artistic location per se. Concrete Comedy isn’t an “artist’s writings” kind of work, it’s a broader cultural document, designed to play in many contexts.ARTBOOK: George Trow has cropped up here and throughout your writings as a mentor figure for you. Can you elaborate a little more on how he fulfilled that role?DR: I sharpened my blade on the stone of Trow, through extensive personal contact. Because I had worked for three of the key minds who had defined an apogee of postwar New York life--Andy Warhol, Plimpton, Diana Vreeland--George identified me as someone who had been trained to further a certain strain of American cultural work which he valued highly, so he took it upon himself to carry my education to the next level. We were quite good friends for some years during the 1980s. Having George in one’s life was like attending a finishing school in American cultural style. He encouraged you to look at the big picture, to scale up your thinking, to look for hidden threads of continuity, and to identify cultural pivot points and evolutionary advances in overlooked or seemingly inconsequential details of the national theater’s past. His writing was an object lesson in using plain, jargon-free language to communicate fancy, culturally ambitious thoughts. Alas, Trow eventually gave up on me. I was a disappointment to him, but then he had been looking for my talents in the wrong places. George is without a doubt the funniest man I’ve ever met but he also regarded himself as the last word on comedy, and no-one is that. He had never considered that, for example, comedy might be expressed purely via material culture. Writing was his sole production, and he never developed the skills to respond to material culture by using the grammars of material culture. I did. Great person, though. I do like to think my friend would approve of Concrete Comedy....ARTBOOK: This raises the subject of your writing style. Readers familiar with the essays, interviews and satires collected in The Velvet Grind will find the same clarity of thought and sentence-making in Concrete Comedy--there’s a generous attention paid to the pacing of ideas and a concern to keep the reader continually in the light (no bad art jargon, no academic miasma, no flab or evasion). A lot of this conceptual clarity seems to take shape in a conversational texture, which suits this particular book very well. But it would be interesting to hear how you go about making your writing.DR: Whether it’s writing, exhibitions, or videos I tend to proceed by identifying something that seems to be missing from the culture and then providing it, or anyway my version of it. My approach is less a matter of “self-expression” than it is a process of surveying the landscape, sniffing the air for a lack or absence of some quality or experience or product that seems to me needed, having faith that other people are unconsciously thirsting for that thing as well, and then arranging for that thing to exist, usually with my own two hands. As Mrs. Vreeland was fond of saying, “Never give people what they want, give them what they don’t know they want.” Sometimes my instincts get it right, sometimes not, but I definitely proceed by instinct, not through analysis, so passion and a palpable existential dimension come across. In written works I’m addressing an external condition rather than an internal, and since it’s not really about me it’s easy to maintain a calm demeanor in the writing. I keep the particulars of the forming thing in front of me and speak to it clearly, to improve its chances for life. As the missing thing and the need for it and the act of providing it are all first sensed or imagined by me, in order to make the case for what I want to introduce into reality I have to make the reader’s contact with my ideas as pleasurable as I’m able. Clarity, simple language, low-key elegance of sentence structure, wit when I can muster it--all of these more than ample opportunities for self-expression, by the way--reward the reader for the attention he’s giving to my aims. Actually, in whatever form I’m working my only real obligation is to deliver on the audience’s attention. It’s the first rule of entertainment. So long as I respect that rule, I’m free to do as I please.Privately, I think of my books as my version of a comedy routine. They don’t follow any of the codes of a comedy routine, and I would never try to convince anyone else to see them that way, but that’s what’s in the back of my mind: a sophisticated comedy routine. They may contain a lot of information and ideas, they may explain a lot, they’re often culturally ambitious and at times high-minded, but even so I always want the reader to come away with an amused, entertained feeling. I don’t want to do anything to obscure that feeling. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to feel that there really is only one subject--love of life--and I don’t want the writing to undercut the subject in any way.ARTBOOK: That really is the only subject (the only subject with legs, at least). Lastly, beyond the topic of books authored by you: can you imagine what a book that covered all aspects of your work to date--art works, comic objects, satires, essays, videos, TV commercials, books--would look like?DR: I’m very invested in the principle of form-discovery--discover the form as you go and build that discovery into whatever you’re making, so that in effect the discovery is the form. It’s half the joy of making things! Until you roll up your sleeves and do that work, you can’t predict what magic you’ll discover or what the best form is for a given project. That said, I think we'd invite writers from different fields--showbiz, comedy, anthropology, visual art, theater, perhaps a novelist--to wrestle with my production. That way we'd have a decent shot at mapping the contours of my cultural location. And then if we could distribute the thing in boxes of cereal, we'd really have something!

Pork Salad Press

Pbk, 6.75 x 9.5 in. / 360 pgs / 2 color / 300 b&w.

| |

|