| RECENT POSTS DATE 2/1/2026 DATE 2/1/2026 DATE 1/31/2026 DATE 1/28/2026 DATE 1/28/2026 DATE 1/25/2026 DATE 1/22/2026 DATE 1/22/2026 DATE 1/21/2026 DATE 1/19/2026 DATE 1/19/2026 DATE 1/18/2026 DATE 1/17/2026

| | | CORY REYNOLDS | DATE 1/9/2017This weekend, the world lost jazz and civil rights champion Nat Hentoff, one of the greatest and most passionate music journalists of all time. In memoriam, we are honored to present Hentoff's eloquently direct text, Jazz Festivals and the Changing of America, from Jim Marshall: Jazz Festival by Reel Art Press.

ABOVE: Nat Hentoff, at the Monterey Jazz Festival, 1961.

JAZZ FESTIVALS AND THE CHANGING OF AMERICA

by Nat Hentoff

This extraordinary book documents, through the brilliant photography of Jim Marshall, one of the most important periods in the cultural history of the United States.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the Newport and Monterey jazz festivals and the battle for civil rights in the South offered starkly contrasting images of America.

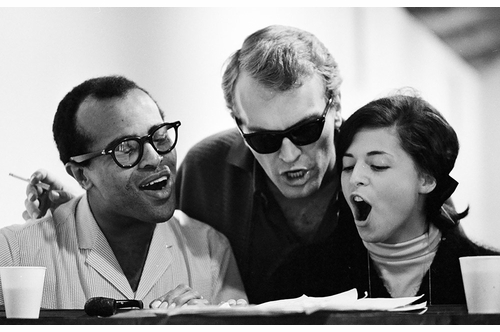

ABOVE: Jon Hendricks, Don Chastain and Carol Sloane at Monterey, 1964.

After World War II, US soldiers who fought fascism abroad returned to an apartheid nation at home. Blacks and whites could be found in the same towns and cities throughout America but they existed in different worlds.

This was true for most of America but especially in the Southern states where segregation of the races was brutally enforced by Jim Crow laws that dictated how and where blacks could live, work, eat, travel, go to the bathroom or even take a drink of water. Imprisonment, beatings and lynchings were the penalties for blacks who disobeyed Jim Crow.

In the North, where segregation laws never took root, social norms made it difficult for blacks and whites to socialize together in public. One notable exception was the bars and music venues where they gathered to listen to jazz, the first uniquely American art form.

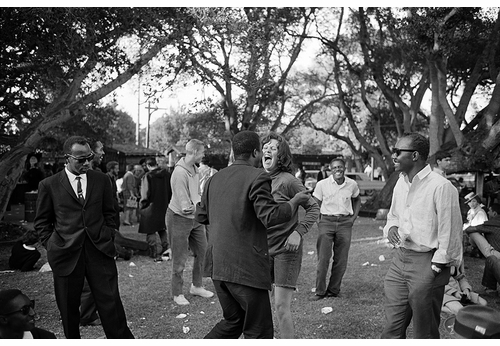

ABOVE: The crowd at Monterey, 1962

Yet jazz clubs that allowed too much race mixing, as it was called at the time, could still expect to be leaned on by local police. In the early 1940s, before I could vote, I often lied my way into Boston's Savoy Café, where I first came to know jazz musicians. It was the only place in town where blacks and whites were regularly on the stand and in the audience. This led police occasionally to go into the men's room, confiscate the soap, and hand the manager a ticket for unsanitary conditions. There was no law in Boston against mixing the races, but it was frowned on in official circles. I used to hear similar complaints from jazz club owners in New York City during the 1950s.

All of this began to change during the summer of 1954. On May 17, the US Supreme Court issued its landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, ruling that segregation was a violation of the US Constitution. On July 11, the first White Citizens' Council was formed in Indianola, Mississippi dedicated to preventing the integration of the South. And on July 17 and 18, the first jazz festival was held in Newport, Rhode Island.

The Citizens' Councils soon spread throughout the South, unleashing a wave of terror directed at non-violent civil rights protestors. While Jim Marshall photographed integrated crowds peacefully digging each other's company at jazz festivals, news photographs of police dogs attacking black men, women and children captured a very different reality in the South.

ABOVE: Monterey, 1961.

The roots of jazz, as well as the roots of the civil rights movement, can be found in the field hollers of slaves reaching out to each other across plantations; gospel songs and prayers connecting slavery here with stories of deliverance of Jews from slavery in the Old Testament; and the blues, the common language of jazz, echoing in Armstrong singing "What did I do to be so black and blue?"

In The Triumph of Music (Harvard University Press) Tim Blanning of Cambridge University tells how black musicians helped prepare America for the civil rights movement. As when opera singer Marian Anderson, denied permission to sing at Constitution Hall by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1939, was invited to instead sing at the Lincoln memorial by Eleanor Roosevelt. She returned to the Lincoln memorial in 1963, during the March on Washington, to sing the spiritual, "He's Got the Whole World In His Hands."

ABOVE: Hentoff at Monterey, 1961.

I was there, at the back of the stage, covering this typhoon of protest for Westinghouse radio, as Mahalia Jackson performed, "I've Been Buked and I've Been Scorned," before she sang out: "Tell them about your dream, Martin!"

Outside of the Newport and Monterey jazz festivals, I had never before seen such a large, integrated crowd coming together for a common purpose. As jazz reached deeply into more white Americans, America began to change.

All photographs reproduced from JIM MARSHALL: JAZZ FESTIVAL by REEL ART PRESS.

Reel Art Press

Hbk, 9.5 x 11.5 in. / 336 pgs / 600 b&w. $49.95 free shipping | |

|