| RECENT POSTS DATE 2/1/2026 DATE 2/1/2026 DATE 1/31/2026 DATE 1/28/2026 DATE 1/28/2026 DATE 1/25/2026 DATE 1/22/2026 DATE 1/22/2026 DATE 1/21/2026 DATE 1/19/2026 DATE 1/19/2026 DATE 1/18/2026 DATE 1/17/2026

| | | CORY REYNOLDS | DATE 4/12/2011Since his first road trip from Oklahoma City to Los Angeles in 1956, West coast Pop artist Ed Ruscha has been influenced by themes and icons surrounding cars, roads, signs and travel. Through the end of this week, the Modern Art Museum Fort Worth presents Ed Ruscha: Road Tested, an exhibition—organized by Chief Curator Michael Auping—which brings together approximately 75 works by Ruscha that explore these themes in a variety of media. Auping's interview with Ruscha, conducted in November, 2009 in Venice, California, is reproduced from the exhibition's stunning new catalog.

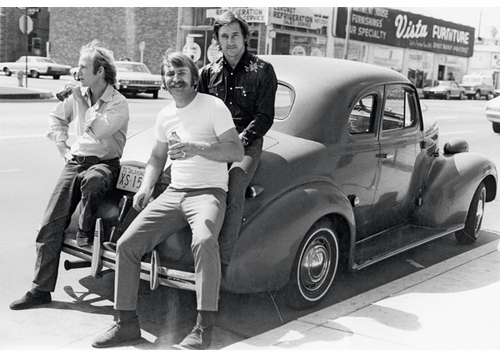

Joe Goode, Jerry McMillan and Ed Ruscha in front of their studios on Western Avenue, Hollywood, 1970.

ED RUSCHA [in the parking area outside his studio] Let me show you something. [Starts up an old black Ford. It's loud and his dog starts barking.]

MICHAEL AUPING It still runs; do you drive it?

E.R. I drive it around the block. I wouldn't want to go very far. The seat is not adjustable and there isn't much room in here.

M.A. Is this the type of car you and Mason Williams drove from Oklahoma City to L.A.?

E.R. No. This is a 1939 Ford. I had a much newer car, a 1950 Ford sedan. It had an adjustable seat, and at the time it seemed luxurious to me. It was my first car. I think I got it in 1953. It was a rite of passage, particularly in those days—to have a car, to be able to go places on your own. It literally became a vehicle to take me places I would dream about. It sounds corny, but I think most people feel that way when they get their first car. I had it a couple of years, drove it around Oklahoma, and then I decided to really give it the road test, and drove it to California with my friend Mason Williams.

M.A. Did it give you any problems during the trip?

E.R. I remember using fourteen quarts of oil on the way. It seemed like we used almost as much oil as we did gas. It was 1956. We didn't eat much. We spent most of our money on fuel. [Walk into the studio]

M.A. How long did it take you to get to California from Oklahoma on that first, long trip west?

E.R. It took about two-and-a-half or three days. Mason kept a log for that trip. I still have it.

M.A. Why did you decide to do a log? It seems kind of formal.

E.R. We kept track of expenses. We were trying to stick to a budget.

M.A. Maybe a better question would be why did you keep the log all these years?

E.R. Mason kept it, and recently returned a copy of it, but why he kept it I'm not really sure. It was a very big trip for a couple of teenagers that didn't know much about anything. It was a long way from Oklahoma. I was in my own car, on my own. It was more than a right of passage. My art, really my life, evolved out of that trip. I wanted to keep the record of some of the things we saw, although it was mostly about how much gas and oil we used, and what we owed each other. I guess there are certain things you keep because of what they represent.

1939 Ford, 1960. Gelatin silver print, 6 x 5 3/8 inches.

M.A. Did you take any photographs on that trip?

E.R. None. I didn't have a camera at that time. The log took the place of photographs. I got a camera soon after arriving in L.A.

M.A. Did you feel like a tourist taking photographs of the city when you first moved to L.A.?

E.R. Probably, but I didn't take a lot of photographs when I first moved here. I was busy just adjusting. Eventually I got curious about why certain things looked like they did, and I used the camera to help me concentrate on them. Actually, I felt more like a reporter than a tourist or an artist. I would give myself assignments, and do a kind of photographic report on certain things that interested me. That's pretty much how the books started.

M.A. Where did you live in L.A. early on?

E.R. Mason and I moved near Lafayette Park, and got into a Mrs. Spears's rooming house on Sunset Place. I was originally going to go to Art Center School, but didn't get in and ended up going to Chouinard. Mason went to L.A. City College. Then he joined the Navy, and I stayed on in L.A.

M.A. Did you keep the car?

E.R. I drove it back to Oklahoma once, and then I sold it there. So I was car-less for about two or three years. I rented a big house with some friends in Hollywood. One of them had a car. So we were sort of okay. We all went to Chouinard, and ironically, all from Oklahoma City.

M.A. It must have been hard not having a car in L.A. It's a big place.

E.R. Things were much different then. I was busy being a student. And in those days, there were trolley cars you could take. The automobile hadn't completely taken over the landscape. We would take the trolley to school, and it got us around on a basic level. Then another friend from Oklahoma came out to L.A., Don Moore, and he had a '54 or '55 Chevy convertible. That was pretty nice.

Ed Ruscha in the Mojave Desert, California, 1962. Photo by Patty Callahan.

M.A. Have you always been interested in cars, and their makes and models?

E.R. Well, I think most people of my generation are. We were the first big automobile generation. I see cars as very efficient and well-designed machines. That photograph you were looking at a minute ago was of Joe Goode's car, another L.A. artist from Oklahoma. It was a 1938 Plymouth. It was a beauty. It had a personality all its own. Cars aren't as interesting as they used to be. They all look alike now.

M.A. Do you like driving?

E.R. I like long car trips, and just driving around. It seems like such a natural, American thing to do. It's a comfortable way to see the world, when there isn't traffic. Flying is convenient, but I'd rather experience things from a car. I did some driving in Europe. It seems like people fly between cities now. So they just see the cities, nothing in between. I also did extensive hitch hiking all over the U.S. since I was 14 years old. But as you might know, hitchhiking is now extinct.

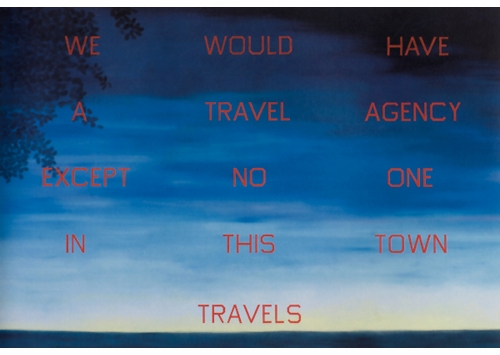

Travel Agency, 1983. Oil on canvas, 80 x 116 inches.

M.A. What took you to Europe?

E.R. The same thing as everyone else probably. I wanted to see what it looked like. I had some great experiences and I had a camera and took quite a few pictures. I was with my mother and my brother. We did that in 1961.

M.A. When you came back from Europe did America seem different? Often when people leave their country for the first time, they come back and see it with new eyes.

E.R. It didn't seem that different. I think what happened was that by exposing myself to a whole other place, I could come back and accept this country for what it was. It wasn't that I didn't like it, but I had nothing to compare it to. Now I could see it for what it was. It gave me a little more clarity, you might say. Also, there are a lot of commonalities. I photographed signs, buildings, and streets. It was another kind of assignment I gave myself to compare how things looked here and there. I loved Europe. I realized how much ground you could cover if you applied yourself. I was looking around at different things every day. It was such a luxury to do that because that was why you were there—to notice details, record what you saw. When I got back, I'm not sure how to describe it, but it seemed like open-road time for me. I wanted to get out and go. I also think the trip to Europe made the western United States seem more exotic to me. There was nothing like it in Europe.

M.A. Are you thinking of L.A. culture and Hollywood?

E.R. Well, there's that, but more about the vastness, the cliché of the wide-open spaces. It really existed. Between Oklahoma and L.A. there seemed to be an empty vastness. There was nothing like that in Europe and even in the U.S. Today it's harder to find. Maybe today it would be like traveling across a remote area of China, or Siberia.

Station, 2003. Acrylic on canvas, 38 1/2 x 72 inches.

M.A. Did that drive between Oklahoma and L.A. get you to start thinking about gas stations as a subject?

E.R. I can't remember not being aware of gas station culture, as I call it. Oklahoma City was a pretty good-sized place, and as a young man you can't help but be fascinated by gas stations, the whole mechanism of it. But it's true, seeing gas stations out on the open road was something else. The loneliness of each one of them, the isolation. When you see them in a city, they are smothered by other businesses. They're part of a dense fabric. Out there they were these islands on a flat plain. They took on a completely different personality.

M.A. I'm sure you were glad to see them out there. They were like an oasis.

E.R. They were. They were like a one- or two-person Western town—a couple of people running the thing, pumping gas, keeping the Coke machine running, stocking what food they had to sell, and working on a couple of cars. Sometimes it was just one guy out there alone. You wonder to yourself if you should stop and then you look at the gas gauge and think "I better stop. I don't know how far it will be until I see another one." It seems silly to talk about it now with gas stations and food places every fifteen miles, but that's not how it was then.

Standard Station with Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half, 1964. Oil on canvas, 65 x 121 1/2 inches.

M.A. Tell me about the film Miracle. Is it about a love story or a car?

E.R. Well, a guy gets distracted from a girl because of this supernatural thing that happens in the garage, and that probably has something to do with my interest in cars but not wanting to get dirty. Typically, you go into the garage to work on your car when you are relatively clean and you have a considered idea of what you are going to do. Then you gradually get dirtier and greasier and things get more chaotic as you take things apart. For me, it would work better if you reversed that. As you work on the car you get cleaner. Then you and the car are both clean and ready to go. That would be a nice miracle.

M.A. Miracle seems kind of clean and well-produced. It doesn't have the rough character of a conceptual art film. It's pretty slick for its day.

E.R. I was never that attracted to what I think of as conceptual video. I wanted to do a movie with actors. I wanted some kind of plot. This was my idea of a Hollywood movie or TV drama.

M.A. Is the plot about the relationship between humans and machines in the form of our relationship to our cars?

E.R. That's a part of it. I also think it has something to do with the art process. A car requires a certain kind of precision in terms of its mechanics. I don't think people are naturally precise like that. We're more intuitive. But art has an engineering or craft or design element to it to make it visually interesting. That element has to come into contact with the intuitive, sometimes sloppy element. When it all works together, it's like a miracle. I appreciate car mechanics. I'm not sure it's an art form, but it's somewhat like that.

M.A. You like to make art, but you don't like to work on cars.

E.R. Sometimes I pretend to do both.

M.A. Because you like to drive, is that an art form to you?

E.R. I like to drive, but I don't know that driving is an art form, unless you mean it in the casual sense or you are talking about a professional situation. I don't think driving is art, but I think it's surreal.

A Blvd. Called Sunset, 1992. Acrylic and tinted varnish on canvas, 84 x 84 inches.

M.A. Do you still enjoy driving around L.A.?

E.R. Maybe not as much as I did in the early days. There's more traffic. At the same time, it's the only way to see L.A., to get the sense that you are in this huge expanse of a city rather than a lot of villages. Driving is the only way to get a handle on it. I drive around L.A. the way New Yorkers enjoy walking their city.

M.A. I assume your books—Some Los Angeles Apartments, Every Building on the Sunset Strip, Thirty-four Parking Lots in Los Angeles, Real- Estate Opportunities—came out of driving around L.A.

E.R. They did, but the chronology of how they developed came out of just wanting to do a book. In school, I had the opportunity to be around a printing press, and I was really fascinated by it— by the mechanics of the press, and by the physical and visual aspects of books. It seemed to me it could be a way of getting a lot of visual information into a single form, completely different than a painting. So while I was working on paintings, there was always a strong urge to make a book. The question was what information to put in it. I wasn't interested in writing a story. So the gas stations as a set of factual pictures basically gave me an excuse to make a small book. I never thought of the gas stations as a story. They were more like fact-images I collected while I was driving. I suppose I could have chosen more dramatic images, but they were exciting enough at the time. It seemed like the right subject for my first book, not because it was so interesting but in a way because it didn't seem too interesting or too personal. Even though I didn't know exactly what I wanted, I knew a lot of things that I didn't want. I didn't want something that was dramatic or sentimental. I just wanted something factual, something that wouldn't distract from the simple, physical economy of the book itself.

M.A. But there must have been something special about the gas stations that attracted you to them in the first place.

E.R. I always liked the architecture of gas stations. They had zoom quality, the way they projected themselves in space. The signs for the stations were lifted up in the air and they really caught your eye, and the gas station was a sleek metal box sitting under it. I loved that roof overhang of a gas station. In those days, it was connected to the office and garage of the station. The way they swept off the building was like a huge wing. It's a very modern, almost abstract image. But they're different, mostly free-standing now, like giant sun and rain canopies. They still have a meaning to me. Maybe the idea that you can create shade with an abstract form. I always thought it would be good to live in one of them. It is a very progressive form of architecture.

M.A. The photographs of the gas stations are pretty small, as is the book. Why not make them bigger if they seemed dramatic?

E.R. That small format seemed like the right size at the time. I'm not sure I could have afforded a bigger book back then. I was paying to publish my own book. I was trying to capture the space as much as the building—the quality of the southwest with few cities and buildings scattered over a huge area.

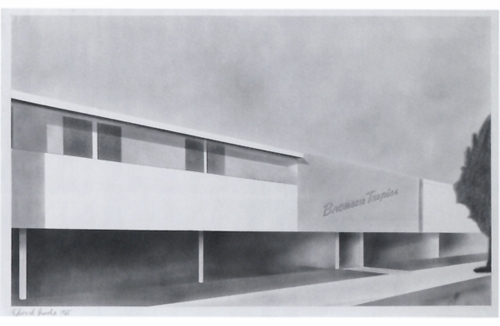

M.A. What about the L.A. apartment buildings? They were presented as relatively small photographs in book format, but then you translated some of them into larger drawings. I think it made them seem a little more special.

E.R. When I first moved here, those kinds of buildings were new to me. I would drive by these apartments and know that they were not well built or even well-designed, but they had a kind of Pop-generic quality, and they became familiar, like a movie set you've seen a hundred times before. Maybe because I would see them more often they got bigger in my mind.

M.A. Did you go looking for apartments like that?

E.R. Not really. They just found me. You don't have to drive very far in L.A. to see one.

Bronson Tropics, 1965. Graphite on paper, 14 1/8 x 22 5/8 inches.

M.A. Did you ever think of any of these books as a pseudo travel journal?

E.R. I didn't think of it that way at the time I was doing them, but looking back on them now, I can sort of see them in that way. People have written me and told me they have traced the routes between them, and then rephotographed them.

M.A. So you never thought of the gas station photographs in terms of a chronological or sequenced narrative.

E.R. No, but there is a pattern to each of the books and that pattern creates its own story visually. They're more strictly visual rather than chronological. I was very clear about not wanting to create any kind of stylistic narrative. When you turned the pages of the book, I wanted you to see something similar, a type, but each one being a little different. What I wanted, and it was more intuitive than anything, was to capture the standardness of it, and at the same time, the difference within the standard.

M.A. Now they have become almost historical documents, hence the fact that people want to go out and find them. It's like they are an unintended form of historic preservation.

E.R. True. It is a kind of travelogue of things that are just starting to be forgotten. People don't look at gas stations now it seems. You just don't notice them like you used to. They're so big and ordinary now. There weren't as many of them before and if you saw one out in the desert where there was nothing else, they suddenly seemed very special. But within the city of L.A. there are far fewer stations today than in the 1950's when there were sometimes three stations at an intersection.

M.A. You seem to have an attraction for ordinary things—gas stations, parking lots, apartment buildings, even empty lots. When you present them in your work, I find myself looking at them as if they were unique.

E.R. They are unique, but within a type that is very common. There is a difference between seeing something from a car and seeing it on foot. In a car, things seem to blur together—another stucco apartment and whoosh —you've passed it. The people who live in those apartments see them differently. It's home to them. To me, it's part of a big stage set to be sorted out. I would imagine myself as a reporter on an assignment. My assignment was to bring back something that I didn't think anyone else had seen.

M.A. Did you pay much attention to light when you took the photographs for the books? They have a bright, harsh quality. Was light a factor in taking the shot or in printing it?

E.R. In the photographs, I wanted to capture a certain reality. When you see something in fairly bright light you see it for what it is. I didn't want any mood lighting. In my paintings, it's different. I think about light in a lot of different ways when I'm making a painting. I like to have the painting surface to have a light-infused look.

M.A. The light often leads to or comes from a horizon, and then a word suggests a place or a thought.

E.R. The horizon paintings partially come out of long drives across the desert. Those are the kinds of drives I really get into. The vastness just asks to be filled with something, and those paintings are a lot about putting a voice into that vastness. When you are driving, you just start thinking about getting to the other side of the horizon— what city do I want to get to; where am I going?

M.A. Are those sunsets a little tongue in cheek?

E.R. Yes and no. When you think of a sunset, you often think of a California sunset, which can be a cliché. But the sunsets here are beautiful, even with the smog, sometimes even better with the smog. My paintings are about that line between the real and the ideal.

M.A. Do you feel the same way about the Hollywood sign?

E.R. Yes. When I lived in Oklahoma, I thought of that sign as a fantasy. When I came to live here, I saw it every day from my studio. It was basically a weather indicator. If I couldn't read it or see it at all, it was a very smoggy day.

M.A. Some of us that have lived in southern California have often used it as a locator. I could get very turned around in that part of the city, and if I could see it, I would be able to get my sense of direction back.

E.R. That's true. It's a good locator.

M.A. It seems like for a while you were obsessed with it.

E.R. It has always had a surreal quality for me. It represents such a huge fantasy, and those giant letters make what is a very undistinguished hill look magical. Then you get behind it, and you see that it is just wooden letters propped up with two by fours. You begin to realize that Hollywood is sublime and silly at the same time. When I moved here, L.A. was a smoggy, overgrown community. At a certain point, it was almost derelict. It has come back, but it was a town that happened to be Hollywood.

M.A. What about Sunset Boulevard—you've referred to that street in a number of works, and you made the book Every Building on the Sunset Strip.

E.R. It has its mythic and reality sides too. It's one of the more interesting streets in Southern California. When you think of Sunset Boulevard, you think of movies stars, but in fact it is an amazing cross-section of the city. I like to recom - mend that people start downtown on Sunset and drive it all the way to the ocean. It's an incredible trail that takes you through wealthy neighbor - hoods and shaky neighborhoods, from urban to ocean, curving streets and straightaways. You see the city from a lot of different angles on that street. I was trying to get a sense of the complete personality of the street when I made the book about the Sunset Strip.

M.A. Your photographs and paintings depict the city from a lot of different perspectives. I think of the overhead view as one of your specialties.

E.R. In L.A., sometimes you feel this need to just get above it because it is so vast and so broad. Also, as a painter, I have always been drawn to oblique overhead views, three-quarter overviews, not directly above, but at an angle. It's an interesting perspective. It exaggerates the space. I think it makes it seem fuller. Some people think looking at the sky gives a more dramatic sense of space, buy I think looking from the sky over the ground is more dramatic. I went up in a helicopter once over L.A. It's very different than experiencing it from a car window. It's a great city to see from the air. It's so horizontal. You can fly directly over the top of the entire city in 45 minutes.

M.A. You have a way of exaggerating the horizontality of landscape. But then you made the mountain paintings. You go vertical in those.

E.R. I almost don't see those as landscapes. They're more like portraits or still lifes. Mountains announce themselves so dramatically, almost symphonically. They are like the orchestra at the beginning of a movie. They are hard to grasp as things. They're more like metaphors for something—heroism or glory.

M.A. And then you put text over them; "La Brea," "Orange Avenue," or "Leroy's Welding."

E.R. I think I'm just trying to humanize the mountains, bring them down to my level.

M.A. And your level is street level.

E.R. Most of the time.

M.A. Do you still drive a lot?

E.R. You have to in L.A. But I prefer drives that are long and desolate. That's the kind of experience I felt when I first drove out West— horizontal and empty. Some people get bored by driving long distances and not seeing any activity. I love it. I see things out there. I let the desert be the inside of my brain, like this space where I can begin to clear my mind, or inventory my mind. When I'm driving in certain rural areas out here in the West I start to make my own Panavision. I'm making my own movie as I'm driving. Images start to show up. I get a lot of information out on the road that I use in my studio. I keep a note pad in the car, and sometimes I write things down or make drawings when I'm driving.

M.A. While you're driving?

E.R. Yes, I've got to where I can write to the side, on the seat without looking at what I'm writing. I'm pretty good at it. Those drawings and notes can be pretty helpful. They're the closest thing I have to a plan.

Hatje Cantz

Hbk, 11 x 9.5 in. / 128 pgs / 128 color.

| |

|