| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

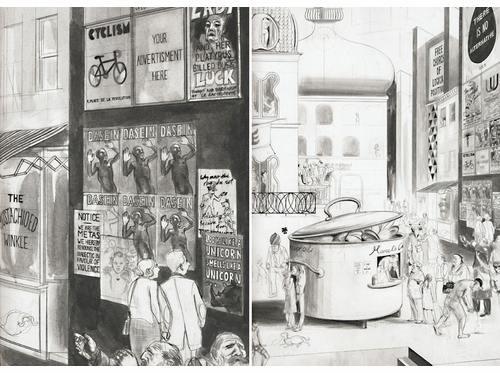

ARTBOOK BLOGEventsStore NewsMuseum Stores of the MonthNew Title ReleasesStaff PicksImage GalleryBooks in the MediaExcerpts & EssaysArtbook InterviewsEx LibrisAt First Sight2025 Gift GuidesFeatured Image ArchiveEvents ArchiveDATE 2/1/2026 Black History Month Reading, 2026DATE 2/1/2026 Join Artbook | D.A.P. at Shoppe Object New York, February 2026DATE 1/31/2026 CULTUREEDIT presents 'Daniel Case: Outside Sex'DATE 1/28/2026 Center for Co-Architecture Kyoto presents 'Archigram: Making a Facsimile – How to make an Archigram magazine'DATE 1/28/2026 Dyani White Hawk offers much needed 'Love Language' in MinneapolisDATE 1/25/2026 Stunning 'Graciela Iturbide: Heliotropo 37' is Back in Stock!DATE 1/22/2026 The groundbreaking films of Bong Joon HoDATE 1/22/2026 ICP presents Audrey Sands on 'Lisette Model: The Jazz Pictures'DATE 1/21/2026 Guggenheim Museum presents 'The Future of the Art World' author András Szántó in conversation with Mariët Westermann, Agnieszka Kurant and Souleymane Bachir DiagneDATE 1/19/2026 Rizzoli Bookstore presents Toto Bergamo Rossi, Diane Von Furstenberg and Charles Miers on 'The Gardens of Venice'DATE 1/19/2026 Black Photojournalism, 1945 to 1984DATE 1/18/2026 Artbook at MoMA PS1 presents Paul M. Farber and Sue Mobley launching 'Monument Lab: Re:Generation'DATE 1/17/2026 Artbook at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles Bookstore presents Peter Tomka on 'Double Player' | THOMAS EVANS | DATE 5/3/2011Charles Avery: Onomatopoeia (Walther König/Koenig Books, London, 2011)Of the many inspired curatorial concepts that Harald Szeemann devised in the course of his career, one of the most suggestive was “individual mythologies.” Szeemann debuted the term as the guiding thesis of the legendary Documenta 5, 1972; he later explicated it (in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist collected in the latter’s A Brief History of Curating) as “intense intentions that can take diverse shapes: people create their own sign systems, which take time to be deciphered.” Nebulously broad as this may sound, what Szeemann intended by “individual mythologies” was an art in which a unified system, or world view or cosmology manifests itself across a range of media—via a repertoire of signs and symbols, as in Marcel Broodthaers’ eagles, pipes and bricks, or Matt Mullican’s generic Isotype symbols; or through allegory, as in the cosmologies of William Blake, or Paul Thek, whom Szeemann included in the 1972 Individual Mythologies show. Such cosmologies would operate independently of existing religious, scientific and philosophical systems (though inevitably borrowing from them).The Island’s port is named Onomatopoeia, and this second volume in what Avery envisages as a multivolume encyclopedia on The Islanders gives a detailed rendering of what the local businesses and flyposter ads around the port of a philosophical allegory might look like:  “If the drawings are compelling, it is because of the sheer effort I got to and my earnest attempt to portray a place to the best of my abilities,” Avery told a recent interviewer. “It’s as though I have an intense conviction about how this place and its people look.” The Islanders differs from other artistic mythologies in which symbolism is often privileged over description, as Avery’s drawing skill takes the enterprise almost to the realm of the virtual in its illustrative zeal; perhaps it also helps obviate the hazard of author-centric solipsism particular to individual mythologies. With each new installment in the project, Avery throws open another vista onto a fresh corner or hinterland of his philosophical playground. |