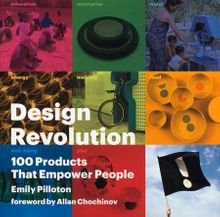

BOOK EXCERPT Design Revolution: 100 Products That Empower PeopleBy Emily Pilloton. Foreword by Allan Chochinov.

| Design Can Change the WorldEmily PillotonAn Industrial Design Revolution I believe that design is problem solving with grace and foresight. I believe that there’s always a better way. I believe that design is a human instinct, that people are inherently optimistic, that every man is a designer, and that every problem can either be defined as a design problem or solved with a design solution. And I believe that in an ideal (design) world, there would be no need for this book, because we as designers would be more responsible and socially productive citizens than we have become. In January 2008, I founded Project H Design based on these ideals with about $1,000 in savings, two design degrees, over $70,000 in student loans, “office space” at the dining room table in my parents’ house, and a lot of frustration with the design world. Project H—a nonprofit organization supporting product design initiatives for humanity, habitats, health, and happiness; one part design firm, one part advocacy group—has seen meteoric growth since then. Our global chapters have worked on projects ranging from water transport and filtration systems to educational devices, retail products co-designed with homeless shelter residents, therapeutic solutions for foster care homes, and more. Partner organizations, a committed board of directors and advisors, and hundreds of volunteers have joined our efforts. Most days Project H’s “headquarters” is wherever there is Wi-Fi and coffee, and I like to think of our global “coalition” as relevant everywhere and based nowhere. As my personal mission has grown into a greater collective drive, Project H has become, I hope, a means to enable designers and enable life through design. Its growth has both surprised me, given my lack of business acumen, and delighted me, proving that I am not alone in my inability to settle for an industrial design career that does nothing but perpetuate the senseless need for, and purchasing of, more stuff. As a whole, today’s world of design (specifically product design) is severely deficient, crippled by consumerism and paralyzed by an unwillingness to financially and ethically prioritize social impact over the bottom line. We need nothing short of an industrial design revolution to shake us from our consumption-for-consumption’s-sake momentum. We must elevate “design for the greater good” beyond charity and toward a socially sustainable and economically viable model taught in design schools and executed in design firms, one that defines the ways in which we prototype, relate to clients, distribute, measure, and understand. We must be designers of empowerment and rewrite our own job descriptions. We must design with communities, rather than for clients, and rethink what we’re designing in the first place, not just how we design the same old things. We must constantly find ways to do things better, through both our designs themselves and the ways in which we operate as designers. On a trip to Cuba in 2000, I became enchanted by the large-scale graphic murals that adorn Havana’s concrete surfaces. They read, “En cada barrio, revolución,” meaning, “In every neighborhood, revolution.” The graphics date to the early 1960s, in the years just following the revolution, when Fidel Castro deployed neighborhood Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR) to monitor the safety, spending, crime, and counterrevolutionary activity within each community block. Most of the murals, which are gorgeous examples of midcentury graphic design, include the CDR’s crestlike symbol, advertising both the omnipresence of “revolution” as an idea and the literal omnipresence of the CDR neighborhood watch¬men. And while the propaganda reeks of a certain “Big Brother” totalitarianism, Cuban citizens tend not to view it that way. The murals’ words are still relevant today, as evidenced by new versions of the motto appearing in contemporary graffiti and street art as statements of national identity and individual rights. During my trip, as I stood admiring one of the murals along El Malecón, the often-photographed seaside road in Havana, an elderly man told me, “They are reminders that we can change things. Revolution is in our blood; it’s who we are. We’ll always fight and try to make our lives better.” His description, in many ways, pinpoints both the need and the motivation for this book. Humans have an instinct to seek out better ways, and designers possess the toolbox (and responsibility) to deliver solutions that make those ways accessible and improve life. As effective designers, we must find efficiencies, bring new function to daily life, and, we hope, do so with some grace or beauty. But our constant search for improvement must extend beyond the things we design to include our own function as designers. Shouldn’t being a designer mean more than the traditional model of object maker and creator of more crap? Shouldn’t we be trusted to make things better? Shouldn’t we be relied upon as problem solvers in times of crisis? I believe that we should and we can, and I hope this book makes the case for the value of such a species of “citizen designers.” In this introduction, you will find three sections that define the context (“Ready . . .”), toolbox (“Set . . .”), and actions (“Go . . .”) required for a design revolution that puts social impact and human needs first. More than 100 examples in this book’s eight categories are evidence of the ability of need-based, humanitarian design to empower and enable individuals, communities, and economies. Design Revolution is both a reference and a roadmap, a call to action and a compendium. The good news is that my personal sentiments are not even remotely uncommon. The tide is turning within design schools, among emerging designers, and in the offices of global design consultancies. Social entrepreneurship has emerged as a business model that effectively supports design for social impact, providing a sustainable economic framework for the distribution of empowering design solutions. Sharing knowledge through information platforms like the Open Architecture Network and the Designers Accord allows us to more efficiently use and learn from each other’s best practices. And global efforts with quantifiable aims, such as the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals, give us something to work toward collectively across disciplines. We have, for perhaps the first time, both the weight of an urgent problem and the power of a collective toolbox to solve some of the biggest global issues. It’s a group effort requiring individual commitments. Let’s rally the troops: In every designer, revolution. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

the source for books on art & culture | CUSTOMER SERVICE Ingram Customer Care 800-937-8200 option 3 orders@dapinc.com NEW YORK LOS ANGELES ARTBOOK LLC All site content Copyright C 2000-2025 by Distributed Art Publishers, Inc. and the respective publishers, authors, artists. For reproduction permissions, contact the copyright holders. The D.A.P. Catalog | ||||||||||||||||||||||||