| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

ARTIST MONOGRAPHS

|

|

STATUS: Forthcoming | 3/3/2026 This title is not yet published in the U.S. To pre-order or receive notice when the book is available, please email orders @ artbook.com |

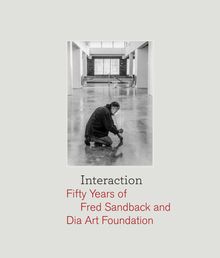

Interaction: Fifty Years of Fred Sandback and Dia Art Foundation

Interaction: Fifty Years of Fred Sandback and Dia Art Foundation

Published by Dancing Foxes Press/Fred Sandback Archive.

Edited by Karen Kelly, Barbara Schroeder. Foreword by Humberto Moro. Text by Lynne Cooke, Julian M. Rose, Corinna Thierolf, Edward A. Vazquez. Conversation with Matilde Guidelli-Guidi, Curtis Harvey.

In 1968, sculptor Fred Sandback (1943–2003) mounted his first solo exhibition at Heiner Friedrich’s Munich gallery, displaying works made from elastic cord or acrylic yarn that traced planes and volumes in space. Thus began a long-term relationship that extended to Dia Art Foundation, the institution cofounded by Friedrich in 1974. Until now, there has been little published on Sandback’s extraordinary alliance with Dia. Essayists Julian M. Rose, Corinna Thierolf and Edward A. Vazquez, as well as conversation partners Matilde Guidelli-Guidi and Curtis Harvey, unearth and explore archival documents, sketches and photographs to reveal how the institution offered Sandback both space and time to meticulously hone his sculptural interventions in the architectural environments of Dia, including the Fred Sandback Museum in Winchendon, Massachusetts, and Dia Beacon, New York.

PUBLISHER

Dancing Foxes Press/Fred Sandback Archive

BOOK FORMAT

Hardcover, 8 x 10 in. / 136 pgs / 168 color / 20 bw.

PUBLISHING STATUS

Pub Date 10/22/2024

Active

DISTRIBUTION

D.A.P. Exclusive

Catalog: FALL 2024 p. 124

PRODUCT DETAILS

ISBN 9781954947122 TRADE

List Price: $35.00 CAD $52.00 GBP £30.00

AVAILABILITY

In stock

in stock $35.00 Free Shipping UPS GROUND IN THE CONTINENTAL U.S. |

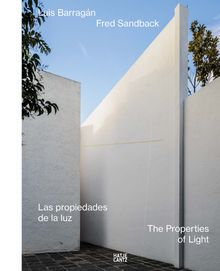

Luis Barragán/Fred Sandback: The Properties of Light

Luis Barragán/Fred Sandback: The Properties of Light

Published by Hatje Cantz.

Text by Federica Zanco, Daniel Garza Usabiaga.

In 2016 sculptures by Fred Sandback (1943–2003) were installed in the Casa Luis Barragán, the Casa Antonio Gálvez, Cuadra San Cristóbal and the Casa Gilardi of Luis Barragán (1902–88). The American minimalist and the Pritzker Prize–winning Mexican architect share a common interest in the properties of light and color; the remarkable interplay between their works, documented in photographs, is presented for the first time in this publication, with essays by Barragán Foundation Director Federica Zanco and curator Daniel Garza Usabiaga, as well as a conversation between architect Roger Duffy, artist Amavong Panya, curator Lilian Tone and author Edward Vazquez.

PUBLISHER

Hatje Cantz

BOOK FORMAT

Hardcover, 9.75 x 12 in. / 160 pgs / 50 color.

PUBLISHING STATUS

Pub Date 3/27/2018

Out of print

DISTRIBUTION

D.A.P. Exclusive

Catalog: SPRING 2018 p. 125

PRODUCT DETAILS

ISBN 9783775743822 TRADE

List Price: $60.00 CAD $79.00

AVAILABILITY

Not available

STATUS: Out of print | 00/00/00 For assistance locating a copy, please see our list of recommended out of print specialists |

Fred Sandback

Published by Steidl.

Edited by James Lawrence.

PUBLISHER

Steidl

BOOK FORMAT

Hardcover, 10 x 12 in. / 128 pgs / illustrated throughout.

PUBLISHING STATUS

Pub Date 11/24/2015

Forthcoming

DISTRIBUTION

D.A.P. Exclusive

Catalog: FALL 2014

PRODUCT DETAILS

ISBN 9783869304564 TRADE

List Price: $85.00 CAD $100.00

AVAILABILITY

Awaiting stock

STATUS: Forthcoming | 11/24/2015 This title is not yet published in the U.S. To pre-order or receive notice when the book is available, please email orders @ artbook.com |

Fred Sandback: Drawing Spaces

Fred Sandback: Drawing Spaces

Published by Kerber.

Edited by Reinhard Spieler, Kerstin Skrobanek. Preface by Reinhard Spieler. Text by Fred Jahn, Kerstin Skrobanek.

PUBLISHER

Kerber

BOOK FORMAT

Paperback, 9.5 x 6 in. / 64 pgs / 43 color.

PUBLISHING STATUS

Pub Date 4/30/2012

Out of print

DISTRIBUTION

D.A.P. Exclusive

Catalog: SPRING 2012 p. 141

PRODUCT DETAILS

ISBN 9783866785588 TRADE

List Price: $29.95 CAD $35.00

AVAILABILITY

Not available

STATUS: Out of print | 00/00/00 For assistance locating a copy, please see our list of recommended out of print specialists |

Fred Sandback: Being in a Place

Fred Sandback: Being in a Place

Published by Hatje Cantz.

Edited by Friedemann Malsch and Christiane Meyer-Stoll. Essays by Yve-Alain Bois and Thierry Davila.

PUBLISHER

Hatje Cantz

BOOK FORMAT

Hardcover, 8 x 10 in. / 296 pgs / 24 color / 120 bw.

PUBLISHING STATUS

Pub Date 3/1/2006

Out of print

DISTRIBUTION

D.A.P. Exclusive

Catalog: SPRING 2006 p. 106

PRODUCT DETAILS

ISBN 9783775717205 TRADE

List Price: $55.00 CAD $65.00

AVAILABILITY

Not available

STATUS: Out of print | 11/28/2010 For assistance locating a copy, please see our list of recommended out of print specialists |