| RECENT POSTS DATE 11/1/2024 DATE 10/27/2024 DATE 10/26/2024 DATE 10/24/2024 DATE 10/21/2024 DATE 10/20/2024 DATE 10/17/2024 DATE 10/16/2024 DATE 10/15/2024 DATE 10/14/2024 DATE 10/10/2024 DATE 10/8/2024 DATE 10/6/2024

| | | CORY REYNOLDS | DATE 10/28/2014In today's New York Review of Books online, J. Hoberman writes, "What Nerve! Alternative Figures in American Art, 1960 to the Present, the provocatively titled exhibit at the RISD Museum in Providence, presents a bracing counter to one prevailing way of telling the story of postwar American art. Somewhat simplified, this traditional account holds that European Surrealism led to Abstract Expressionism, which led to Pop Art and Minimalism, which were followed by Earth Art, Body Art, and Conceptual Art, the return of expressive painting, and so on up to the present, when no one city nor any single movement reigns supreme: a thousand flowers bloom."

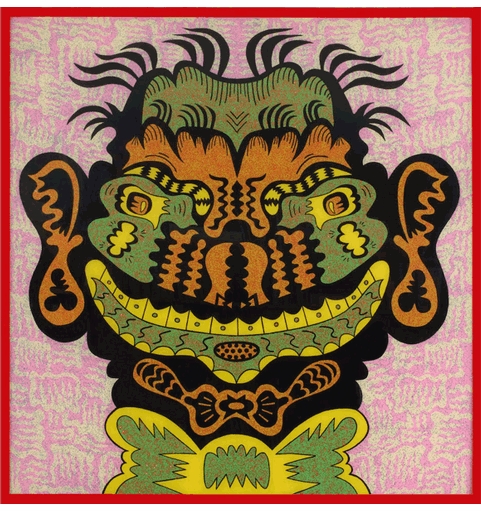

Karl Wirsum: "Junior Messing with the Kid" (1968)

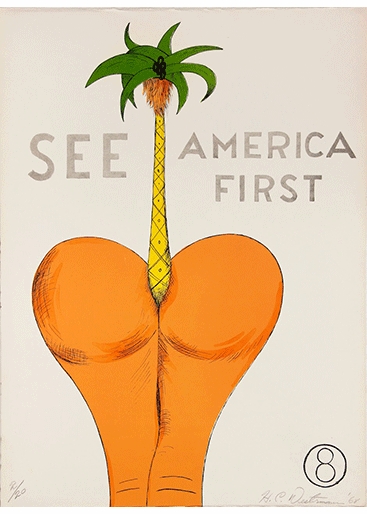

But What Nerve!, organized by Dan Nadel with Judith Tannenbaum, argues that it was ever thus, and in Nadel’s words, “proposes an alternate history of figurative painting, sculpture and vernacular image-making that has been largely overlooked and undervalued relative to the canon of Modernist abstraction and Conceptual art.” There’s a healthy truculence to the premise and much of the work as well. Indeed, the show immediately engages the eye with two bumptious works of dissident splendor. The seventeen lithographs of H.C. Westermann’s corrosive, cartoony See America First series, stripped down travel posters for a dead land, get an additional zetz of Coney Island sensationalism from their proximity to Peter Saul’s blithely outrageous, biomorphic construction in enamel and plastic coated Styrofoam, Man in Electric Chair (1966).

As What Nerve! shows, mutated versions of Surrealism and Pop Art and tendencies without a name arose and flourished outside of New York and Los Angeles throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s in the work of groups such as Chicago’s Hairy Who (most active in the mid 1960s), Detroit’s Destroy All Monsters (which coalesced a decade later), Providence’s Forcefield (who came together in the 1990s), and the Bay Area 'funk' artists (named for a 1967 museum show and less a clique than a curator-defined association). Many attended art school together. Young and defiantly provincial, these artists were represented by small galleries or none at all. They made their own scenes, working in styles antithetical to the established canon. As precursors or fellow travelers the show proposes six additional figures: William Copley, Elizabeth Murray, Christina Ramberg, H.C. Westermann, painter-cartoonist-designer Gary Panter, and, most radically, comic-book illustrator Jack Kirby—all (save Murray) figurative artists, flirting with the outré or crackpot in making use of caricature, outsider art, doodles, and other vernacular styles.

Generally speaking, the art is grotesque, garish and exuberant, cranky, sometimes menacing, often hilarious and, in the case of the Hairy Who and Destroy All Monsters, particularly fresh. Much could be considered representational, albeit with a fondness for squiggly, tubular forms and faces that suggest something splattered against a wall. Vectors abound. Hairy Who member Karl Wirsum’s near-psychotic images of trippy, patterned faces are placed in dialogue with Kirby’s painstaking ink and water-color portraits of nascent super-heroes.

A visiting art class spent almost their entire time in the gallery in the Kirby corner the day I was there. At once the most commercial and most outside artist in the show, Kirby apparently made these studies for himself. The earliest, Metron (1969), is, upon close examination, an extremely fastidious collage; another, the intricately patterned, immaculately detailed, elegantly robo-Cubist Dream Machine (1970-75) confounds description as well as scale. (Epic by comic book standards, it has a pleasingly miniaturized feel as a framed painting.)

The fetish quality evident in Kirby’s work is present in much of the show. In somewhat opposing ways, Copley and Ramberg reference porn magazines. In its juxtaposition of sci-fi props and Andean costumes, Forcefield’s work seems conceived under the spell of Erich von Daniken, the Swiss author of best-selling books suggesting extraterrestrial influence on early human culture. Not just the work of deserved art stars Mike Kelley and Jim Shaw (makers of drawings, collages and mixed media assemblages)—but just about everything associated with Destroy All Monsters is perfumed with eau of Salvation Army thrift store: a wall of Cary Loren’s distressed photographs, many of them costumed glamor shots, segues into the non-ironic goth art of his frequent subject Niagara, inventor of her own pre-Raphaelite art brut.

H. C. Westermann: "See America First" (1968)

The Hairy Who and Destroy All Monsters both produced zines, on display in vitrines. It must have been hard for Nadel, the editor of two exemplary anthologies of obscure or underappreciated comic- book artists, Art Out of Time: Unknown Visionary Cartoonists, 1900-1969 and Art in Time: Unknown Comic Book Adventures, 1940-1980, not to display their contents, which, among other things, include comic strips by the great Jim Nutt, whose painted splash page Backman (1966) is one of the show’s glories.

Still, to open up the zine would have been to open up the show to another direction, suggesting a parallel to the first wave of underground cartoonists—less R. Crumb than Robert Williams’s impacted chrome-scapes or the sex mandalas of psychedelic primitive Rory Hayes, an artist whose work Nadel has edited. Similarly, Gary Panter links not just to Kirby, whom he has acknowledged as an influence, but to the commercial collective that created Pee-wee’s Playhouse and the cohort of cartoonists published in RAW magazine, two 1980s artists’ groups in which he played a significant part.

To point this out is in no way a criticism of What Nerve! Ken Johnson said as much in his New York Times review, which also ended by suggesting related artists, to which I would add, looking forward by way of Elizabeth Murray, the painter-cartoonist Amy Sillman and back, through Loren’s photographs, the underground polymath Jack Smith, whom he sought out as a young artist. The urge to contribute to What Nerve! is a tribute to this super-charged show’s inspiring revisionist splendor.

RISD Museum of Art/D.A.P.

Pbk, 8.75 x 10.5 in. / 368 pgs / 300 color.

| |

|