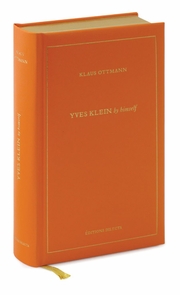

KLAUS OTTMANN | DATE 8/18/2010

Yves Klein (1928-1962) was an agitator of ideas, a

total artist who used his considerable charisma to propagate social

change through art. In his writings and talks, Klein drew on a vast

repertoire of philosophical, scientific, political and occult

materials, synthesizing them into a declamatory propaganda for his own

art. Yves Klein by Himself is a composite biography of one of

the most influential artists of the second half of the twentieth

century. Neither an intellectual biography nor an art-historical

analysis, Yves Klein by Himself is rather a kind of "Klein

reader" that lets the artist speak through his ideas and philosophical

conceptions, and in doing so attempts to reconstruct his "organized

network of obsessions." To this end, it intermixes biographical facts,

a selection of texts by the writers and artists who influenced Klein, a

glossary of keywords with Klein's own definitions derived from

published texts as well as previously unpublished manuscripts and a

selection of critical writings with analyses of Klein's philosophical

ideas by the author and editor of this volume, Klein scholar Klaus

Ottmann.

The following excerpt, from Chapter V, presents Ottmann's brilliant explication of Klein's "ethics" of style.

V: Grace into Style

Style is the general necessity seen sub specie aeterni.

– Ludwig Wittgenstein

Style is the ultimate morality of mind.

– Alfred North Whitehead

When Yves Klein arrived in New York to show his blue monochromes at Leo Castelli’s gallery in 1961, the New York art world objected not so much to his work than to his style. For years to come, American reviewers continued to focus on Klein’s appearance, dismissing him as an “entertainer and idea man.” American Pop art, as Roland Barthes observed so keenly, was anti-style; it was about neutralizing identity:

"Pop art is well aware that the fundamental expression of the person is style. As Buffon said (a celebrated remark, once known to every French schoolboy): “Style is the man.” Take away style and there is no longer any (individual) man. The notion of style, in all the arts, has therefore been linked, historically, to a humanism of the person... There is, as I see it, a certain relation between pop art and what is called “script,” that anonymous writing style sometimes taught to dysgraphic children because it is inspired by the neutral and, so to speak, elementary features of typography. Further, we must realize that if pop art depersonalizes, it does not make anonymous: nothing is more identifiable than Marilyn...; they are in fact nothing but that: ...teaching us that identity is not the person: the future world risks being a world of identities... but not of persons."

Klein’s emphasis on style must be viewed in the context of the French notion of civilization. Unlike his contemporaries, especially the Teutonic-shamanistic Joseph Beuys or the orgiastic Viennese actionists Otto Mühl and Hermann Nitzsch, Klein always presented himself and his art in a proper, civilized manner – notably during his performances of the Anthropometries, when he directing his “living brushes” from a distance like a Master of Ceremonies, never touching the models or the paintings with his own hands.

In 1828 the historian and future Prime Minister of France, François Guizot announced, in his lectures on the “The General History of Civilization in Europe,” that “France has been... the home of civilization in Europe,” and, by 1852, when Alphonse de Lamartine, the nineteenth-century poet and politician, founded the journal Le Civilisateur, civilization had become synonymous with France.

Unlike Beuys in Germany and Klein in France, Andy Warhol shifted artistic personality from himself onto his objects, or even his critics (he would frequently tell interviewers to write his answers to their questions). Klein’s style is an essential part of his art and of its humanism. Even when he yielded the actual production of a painting to his models during the making of his Anthropometries, he never conceded his role as an artist. His presence in these performances was essential, very unlike the modus operandi of Warhol who would simply turn on his film camera and walk away, letting those in front of the camera take control. (“I make nothing happen.”)

Wittgenstein’s famous dictum that “ethics and aesthetics are one” has to be read in the context of the philosopher’s understanding of philosophy as a living practice. Ethics includes an aesthetical component, and vice versa. For Wittgenstein – as for Nietzsche before him – art and morality are closely tied. All aesthetic activity is also ethical, just as philosophy is a practice of life, a Lebensphilosophie. It is through style that philosophical and aesthetical practices become authentic. Philosophy and art are forms of life:

"To imagine a language means to imagine a form of life [Lebensform]."

Language is an activity or a form of life: “The term “language-game” is meant to bring into prominence the fact that the speaking of language is part of an activity, or of a form of life.”

Wittgenstein’s note about style that serves as an epigraph to this chapter was written in the 1930s but is directly related to a remark found in his notebooks of 1915–16:

"The work of art is the object seen sub specie aeternitatis; and the good life is the world seen sub specie aeternitatis. This is the connection between art and ethics."

Both remarks relate to a reference in Spinoza’s Ethics to “sub specie aeternitatis” (under the aspect of eternity, i.e., universally and eternally true), which Spinoza links to human freedom. Hegel writes about Spinoza’s Ethics that there is “no purer and loftier morality... ; the eternal truth is man’s sole purpose for his actions.” In Book II of his Ethics, Spinoza introduces the notion of ideas as active concepts rather than passive perceptions (at conceptus actionem mentis exprimere videtur) and ties these active ideas to man’s free will (libera voluntas).

In a letter to the Austrian publisher Ludwig von Ficker, Wittgenstein writes that the meaning of his Tractatus is “ethical,” and that the work consists of two parts – a written and an unwritten one:

"My work consists of two parts: what is on hand and everything I did not write. And it is precisely this second part that is most important. The Ethical is quasi defined from within by my book."

Style endows language and art with authenticity: it gives them an authentic voice, grounds them in life. For Klein, as for Wittgenstein, the work consists of two parts: one is materialized in the pigment; the other is immaterial, lived, or enacted in performances. Style is not a fashioning of power to attain a desired end but an ethical practice: to exist as a living work of art[.]